A hacker took control of a computer network at the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency in November. The day after Thanksgiving, reports Popular Mechanics, ticketing kiosks on the San Francisco light rail went offline as agency screens displayed, “You Hacked, ALL Data Encrypted. Contact For Key(cryptom27@yandex.com)ID:681 ,Enter.” The hacker at that address said the decryption key would cost 100 bitcoins, or about $73,000, delivered by Tuesday. And it turns out the most surprising thing about this incident is that it hasn't happened before.

It's hard to get precise numbers on cyberattacks, since they rely on disguising themselves, but available data for ransomware paints a grim picture. A June 2016 study by Osterman research and security firm Malwarebytes found that 47 percent of U.S. enterprises — businesses, hospitals, schools, government agencies — had been infected with ransomware at least once in the previous year. Among U.K. respondents, 12 percent had been hit at least six times. Globally, 37 percent of organizations paid.

Advertisement

Home users might be in even worse shape. Of the more than 2.3 million users of Kaspersky Labs security products who encountered ransomware between April 2015 and March 2016, almost 87 percent were at home. No word on how many paid up, but with ransoms averaging a few hundred dollars, and ransomware proceeds estimated at $209 million for the first three months of 2016, it was probably quite a few.

The Biggest Thing in Malware

“Ransomware has been promoted from one of many techniques used by attackers to one of [the] most effective tools in their toolbox,” writes Andrew Howard, chief technology officer at Kudelski Security, in an email. “It is somewhat surprising to me that it took attackers until now to leverage this type of technique.”

“Other types of malware are still common,” Howard writes, “but they lack the financial benefits of ransomware.”

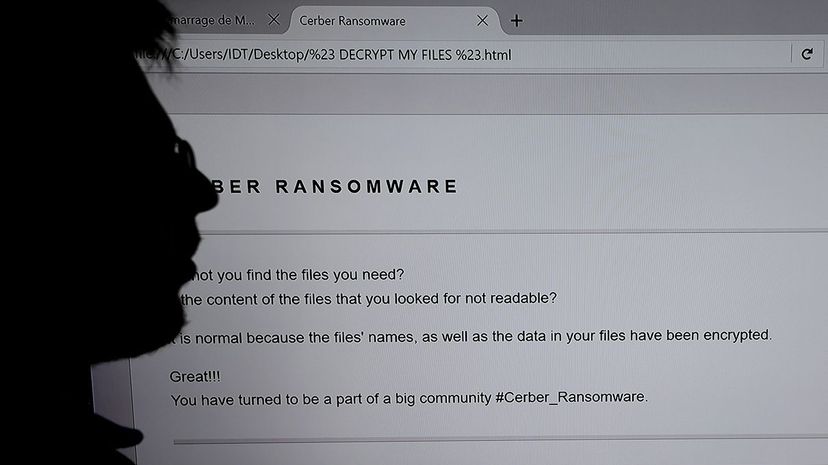

Attacks are brilliantly simple: A computer user falls for a phishing email or stumbles on a corrupted web page, and a malicious piece of software downloads. It encrypts (or otherwise blocks access to) the computer's files, and the infection spreads from that computer to any other computer connected to it. The hacker announces him- or herself, provides a method of contact and promises the decryption key in exchange for payment, typically in a digital “cryptocurrency” like Bitcoin or MoneyPak, which is harder to trace than cash.

The sheer volume of attacks is staggering. U.S. Homeland Security estimates an average of 4,000 per day in 2016, up 300 percent from the previous year.

Joe Opacki, vice president of threat research at PhishLabs, says ransomware “has transformed how cybercriminals make money.”

“Instead of having to steal data and sell it or rent out botnets to other cybercriminals, ransomware offers direct payment,” Opacki writes in an email. “You infect a computer and the victim pays you. No additional steps, no middlemen taking their cut ...”

This is not a new concept. Early versions of the scheme date back to 1989, when hackers distributed the AIDS Trojan horse through snail mail via infected floppy disks. The program, believed to be part of a global extortion scheme, encrypted part of a PC's root directory.

That malware pioneer was quickly defeated. But decades have fine-tuned both delivery and encryption methods.

Ransomware Done Right

Nolen Scaife, information-systems doctoral student at the University of Florida (UF) and research assistant at the Florida Institute for Cybersecurity Research, says ransomware is a tough adversary.

“Defending against this kind of attack is tremendously difficult, and we are only now starting to see plausible defenses for ransomware,” Scaife writes.

Ransomware attacks “differ slightly each time they occur,” he explains, making them difficult to detect and disable. Further complicating matters, ransomware activity in a system can resemble legitimate actions an administrator might perform.

Scaife's team at UF developed a ransomware-detection program called CryptoDrop, which “attempts to detect the ransomware encryption process and stop it.” The less data the malware can encrypt, the less time spent restoring files from backup.

But reversing the encryption is a different story. According to Scaife, well-designed ransomware can be unbreakable.

“The reliability of good cryptography done properly and the rise of cryptocurrency have created a perfect storm for ransomware,” Scaife writes in an email. “When the ransomware is created correctly and if there are no [data] backups, the only way to get back the victim's files is to pay the ransom.”

Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center in Los Angeles held out for almost two weeks before paying 40 bitcoins (about $17,000) to decrypt its communications systems in February 2016. The hacker never had access to patient records, reports Newsweek's Seung Lee, but staff were filling out forms and updating records with pencil and paper for 13 days.

In March, ransomware hit networks at three more U.S. hospitals and one in Ottawa, Ontario; and another Ontario hospital had its website hacked to infect its visitors with the malware.

Targeted Attacks

Hospitals are perfect victims, security expert Jérôme Segura told CBC News. "Their systems are out of date, they have a lot of confidential information and patient files. If those get locked up, they can't just ignore it."

Same with law enforcement. At least one of the five Maine police departments hit by ransomware in 2015 was running DOS, the chief told NBC.

Police departments are popular targets. And while the irony of the situation is lost on no one, police are as likely to pay as anyone else. A New Hampshire police chief who couldn't bear it got a bright idea: He paid the ransom, got the key, and cancelled payment; but when his department got hit again two days later he just forked over the 500 bucks.

A school district in South Carolina paid $8,500 in February 2016. The University of Calgary paid $16,000 in June, explaining it couldn't take risks with the “world-class research” stored on its networks. In November, a few weeks before the light-rail hack, an Indiana county paid $21,000 to regain access to systems at its police and fire departments, among other agencies.

Reports on the light-rail attack suggest an uncommon approach. It appears the ransomware was released from within the system. Opacki says the hacker seems to have exploited “a known vulnerability in Oracle's WebLogic software ... The attacker was likely scanning the internet for this sort of known vulnerability and came across SFMTA's system opportunistically.”

Once inside, the hacker introduced the ransomware.

“But most ransomware attacks don't happen this way,” Opacki writes. Usually, the vulnerability is in people, not software.

“It's Disheartening”

“As a general rule,” notes Opacki, “people overestimate their ability to spot a phishing scam.”

Indeed, a 2016 study found that 30 percent of people open phishing emails, and 13 percent of those then click on the attachment or link.

“Many people still think that phishing attacks are poorly designed spam emails rife with spelling issues and broken English. Then they try to open an ‘employee payroll' spreadsheet that they believe HR sent them by mistake,” Opacki writes.

Phishing has come a long way since Nigerian princes needed our help with their money. Many emails are personalized, using real details about would-be victims, often gleaned from social-media postings.

In the experience of Kudelski's Andrew Howard, “in the most security conscious organizations ... 3 to 5 percent of employees are fooled even by the most poorly conceived phishing scams. The numbers at less security conscious organizations, or with more sophisticated scams, are much worse.”

“It is rather disheartening,” he adds.

Yet the staggering rise of ransomware attacks in the last few years has less to do with gullibility, or even great malware design, than with ease. Running a ransomware scam is about as complex as mugging someone on the street, but a lot less risky.

Hacking for Idiots

There's not much skill involved in ransomware, according to Nolen Scaife. The software isn't that sophisticated. Hackers can create it quickly and deploy it successfully without much effort.

More important, though, hackers don't have to create the ransomware to deploy it. They don't even have to know how to create it.

Most people running ransomware scams bought the software on the internet underworld known as the dark web, where ransomware developers sell countless variants in sprawling malware marketplaces. It comes as all-in-one apps, often complete with customer service and tech support to help scams run smoothly.

“Support and service,” writes Dan Turkel on Business Insider, “are particularly important to sellers whose market is comprised of relatively inexperienced hackers who may need some degree of hand-holding,”

Some products come with money-back guarantees, Turkel writes. Many offer call-in or email services that walk defeated victims through payment and decryption, so the hacker doesn't have to deal with it. At least one family of ransomware provides this “customer service” via live chat.

The ransomware market is so robust, developers are employing distributors to sell their products.

None of this bodes well for anyone not running the scam. According to every cybersecurity expert everywhere, we should all back up our stuff. Without backups, paying the ransom might be only choice if we ever want to see our data again.

And even then, we still may not be reunited with our data. A Trend Micro study found that 20 percent of the U.K. businesses that paid ransoms in 2016 never received a key.

The San Francisco transit bureau didn't pay anything. A spokesperson told Fortune the agency never considered it. Systems were restored from backups, with most back online within two days. In the meantime, San Franciscans rode the light rail for free.

Two days later, hackers hacked the email account of the light-rail hacker, revealing an estimated $100,000 in ransomware payments since August.

Advertisement