Strings in C are intertwined with pointers to a large extent. You must become familiar with the pointer concepts covered in the previous articles to use C strings effectively. Once you get used to them, however, you can often perform string manipulations very efficiently.

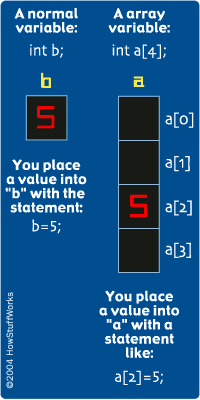

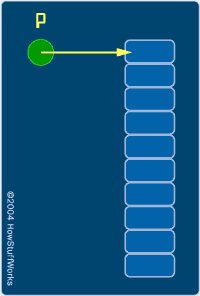

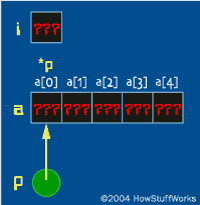

A string in C is simply an array of characters. The following line declares an array that can hold a string of up to 99 characters.

It holds characters as you would expect: str[0] is the first character of the string, str[1] is the second character, and so on. But why is a 100-element array unable to hold up to 100 characters? Because C uses null-terminated strings, which means that the end of any string is marked by the ASCII value 0 (the null character), which is also represented in C as '\0'.

Null termination is very different from the way many other languages handle strings. For example, in Pascal, each string consists of an array of characters, with a length byte that keeps count of the number of characters stored in the array. This structure gives Pascal a definite advantage when you ask for the length of a string. Pascal can simply return the length byte, whereas C has to count the characters until it finds '\0'. This fact makes C much slower than Pascal in certain cases, but in others it makes it faster, as we will see in the examples below.

Because C provides no explicit support for strings in the language itself, all of the string-handling functions are implemented in libraries. The string I/0 operations (gets, puts, and so on) are implemented in <stdio.h>, and a set of fairly simple string manipulation functions are implemented in <string.h> (on some systems, <strings.h> ).

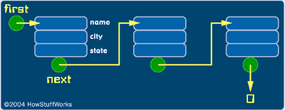

The fact that strings are not native to C forces you to create some fairly roundabout code. For example, suppose you want to assign one string to another string; that is, you want to copy the contents of one string to another. In C, as we saw in the last article, you cannot simply assign one array to another. You have to copy it element by element. The string library (<string.h> or <strings.h> ) contains a function called strcpy for this task. Here is an extremely common piece of code to find in a normal C program:

char s[100];

strcpy(s, "hello");

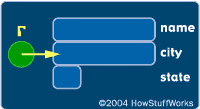

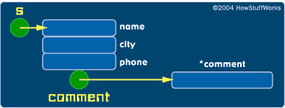

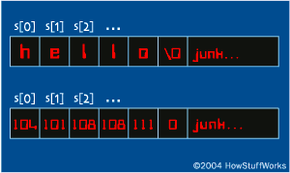

After these two lines execute, the following diagram shows the contents of s:

The top diagram shows the array with its characters. The bottom diagram shows the equivalent ASCII code values for the characters, and is how C actually thinks about the string (as an array of bytes containing integer values). See How Bits and Bytes Work for a discussion of ASCII codes.

The following code shows how to use strcpy in C:

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

char s1[100],s2[100];

strcpy(s1,"hello"); /* copy "hello" into s1 */

strcpy(s2,s1); /* copy s1 into s2 */

return 0;

}

strcpy is used whenever a string is initialized in C. You use the strcmp function in the string library to compare two strings. It returns an integer that indicates the result of the comparison. Zero means the two strings are equal, a negative value means that s1 is less than s2, and a positive value means s1 is greater than s2.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

char s1[100],s2[100];

gets(s1);

gets(s2);

if (strcmp(s1,s2)==0)

printf("equal\n");

else if (strcmp(s1,s2)<0)

printf("s1 less than s2\n");

else

printf("s1 greater than s2\n");

return 0;

}

Other common functions in the string library include strlen, which returns the length of a string, and strcat which concatenates two strings. The string library contains a number of other functions, which you can peruse by reading the man page.

To get you started building string functions, and to help you understand other programmers' code (everyone seems to have his or her own set of string functions for special purposes in a program), we will look at two examples, strlen and strcpy. Following is a strictly Pascal-like version of strlen:

int strlen(char s[])

{

int x;

x=0;

while (s[x] != '\0')

x=x+1;

return(x);

}

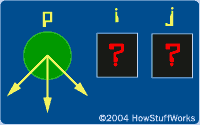

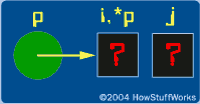

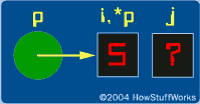

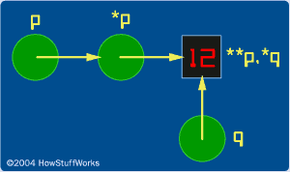

Most C programmers shun this approach because it seems inefficient. Instead, they often use a pointer-based approach:

int strlen(char *s)

{

int x=0;

while (*s != '\0')

{

x++;

s++;

}

return(x);

}

You can abbreviate this code to the following:

int strlen(char *s)

{

int x=0;

while (*s++)

x++;

return(x);

}

I imagine a true C expert could make this code even shorter.

When I compile these three pieces of code on a MicroVAX with gcc, using no optimization, and run each 20,000 times on a 120-character string, the first piece of code yields a time of 12.3 seconds, the second 12.3 seconds, and the third 12.9 seconds. What does this mean? To me, it means that you should write the code in whatever way is easiest for you to understand. Pointers generally yield faster code, but the strlen code above shows that that is not always the case.

We can go through the same evolution with strcpy:

strcpy(char s1[],char s2[])

{

int x;

for (x=0; x<=strlen(s2); x++)

s1[x]=s2[x];

}

Note here that <= is important in the for loop because the code then copies the '\0'. Be sure to copy '\0'. Major bugs occur later on if you leave it out, because the string has no end and therefore an unknown length. Note also that this code is very inefficient, because strlen gets called every time through the for loop. To solve this problem, you could use the following code:

strcpy(char s1[],char s2[])

{

int x,len;

len=strlen(s2);

for (x=0; x<=len; x++)

s1[x]=s2[x];

}

The pointer version is similar.

strcpy(char *s1,char *s2)

{

while (*s2 != '\0')

{

*s1 = *s2;

s1++;

s2++;

}

}

You can compress this code further:

strcpy(char *s1,char *s2)

{

while (*s2)

*s1++ = *s2++;

}

If you wish, you can even say while (*s1++ = *s2++);. The first version of strcpy takes 415 seconds to copy a 120-character string 10,000 times, the second version takes 14.5 seconds, the third version 9.8 seconds, and the fourth 10.3 seconds. As you can see, pointers provide a significant performance boost here.

The prototype for the strcpy function in the string library indicates that it is designed to return a pointer to a string:

char *strcpy(char *s1,char *s2)

Most of the string functions return a string pointer as a result, and strcpy returns the value of s1 as its result.

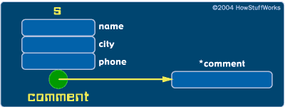

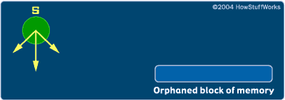

Using pointers with strings can sometimes result in definite improvements in speed and you can take advantage of these if you think about them a little. For example, suppose you want to remove the leading blanks from a string. You might be inclined to shift characters over on top of the blanks to remove them. In C, you can avoid the movement altogether:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

char s[100],*p;

gets(s);

p=s;

while (*p==' ')

p++;

printf("%s\n",p);

return 0;

}

This is much faster than the movement technique, especially for long strings.

You will pick up many other tricks with strings as you go along and read other code. Practice is the key.