Dynamic Data Structures: Malloc and Free

Let's say that you would like to allocate a certain amount of memory during the execution of your application. You can call the malloc function at any time, and it will request a block of memory from the heap. The operating system will reserve a block of memory for your program, and you can use it in any way you like. When you are done with the block, you return it to the operating system for recycling by calling the free function. Then other applications can reserve it later for their own use.

For example, the following code demonstrates the simplest possible use of the heap:

Advertisement

int main()

{

int *p;

p = (int *)malloc(sizeof(int));

if (p == 0)

{

printf("ERROR: Out of memory\n");

return 1;

}

*p = 5;

printf("%d\n", *p);

free(p);

return 0;

}

The first line in this program calls the malloc function. This function does three things:

- The malloc statement first looks at the amount of memory available on the heap and asks, "Is there enough memory available to allocate a block of memory of the size requested?" The amount of memory needed for the block is known from the parameter passed into malloc -- in this case, sizeof(int) is 4 bytes. If there is not enough memory available, the malloc function returns the address zero to indicate the error (another name for zero is NULL and you will see it used throughout C code). Otherwise malloc proceeds.

- If memory is available on the heap, the system "allocates" or "reserves" a block from the heap of the size specified. The system reserves the block of memory so that it isn't accidentally used by more than one malloc statement.

- The system then places into the pointer variable (p, in this case) the address of the reserved block. The pointer variable itself contains an address. The allocated block is able to hold a value of the type specified, and the pointer points to it.

The program next checks the pointer p to make sure that the allocation request succeeded with the line if (p == 0) (which could have also been written as if (p == NULL) or even if (!p). If the allocation fails (if p is zero), the program terminates. If the allocation is successful, the program then initializes the block to the value 5, prints out the value, and calls the free function to return the memory to the heap before the program terminates.

There is really no difference between this code and previous code that sets p equal to the address of an existing integer i. The only distinction is that, in the case of the variable i, the memory existed as part of the program's pre-allocated memory space and had the two names: i and *p. In the case of memory allocated from the heap, the block has the single name *p and is allocated during the program's execution. Two common questions:

- Is it really important to check that the pointer is zero after each allocation? Yes. Since the heap varies in size constantly depending on which programs are running, how much memory they have allocated, etc., there is never any guarantee that a call to malloc will succeed. You should check the pointer after any call to malloc to make sure the pointer is valid.

- What happens if I forget to delete a block of memory before the program terminates? When a program terminates, the operating system "cleans up after it," releasing its executable code space, stack, global memory space and any heap allocations for recycling. Therefore, there are no long-term consequences to leaving allocations pending at program termination. However, it is considered bad form, and "memory leaks" during the execution of a program are harmful, as discussed below.

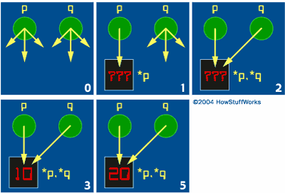

The following two programs show two different valid uses of pointers, and try to distinguish between the use of a pointer and of the pointer's value:

void main()

{

int *p, *q;

p = (int *)malloc(sizeof(int));

q = p;

*p = 10;

printf("%d\n", *q);

*q = 20;

printf("%d\n", *q);

}

The final output of this code would be 10 from line 4 and 20 from line 6.

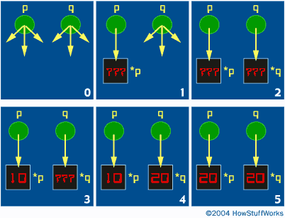

The following code is slightly different:

void main()

{

int *p, *q;

p = (int *)malloc(sizeof(int));

q = (int *)malloc(sizeof(int));

*p = 10;

*q = 20;

*p = *q;

printf("%d\n", *p);

}

The final output from this code would be 20 from line 6.

Notice that the compiler will allow *p = *q, because *p and *q are both integers. This statement says, "Move the integer value pointed to by q into the integer value pointed to by p." The statement moves the values. The compiler will also allow p = q, because p and q are both pointers, and both point to the same type (if s is a pointer to a character, p = s is not allowed because they point to different types). The statement p = q says, "Point p to the same block q points to." In other words, the address pointed to by q is moved into p, so they both point to the same block. This statement moves the addresses.

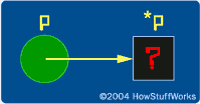

From all of these examples, you can see that there are four different ways to initialize a pointer. When a pointer is declared, as in int *p, it starts out in the program in an uninitialized state. It may point anywhere, and therefore to dereference it is an error. Initialization of a pointer variable involves pointing it to a known location in memory.

- One way, as seen already, is to use the malloc statement. This statement allocates a block of memory from the heap and then points the pointer at the block. This initializes the pointer, because it now points to a known location. The pointer is initialized because it has been filled with a valid address -- the address of the new block.

- The second way, as seen just a moment ago, is to use a statement such as p = q so that p points to the same place as q. If q is pointing at a valid block, then p is initialized. The pointer p is loaded with the valid address that q contains. However, if q is uninitialized or invalid, p will pick up the same useless address.

- The third way is to point the pointer to a known address, such as a global variable's address. For example, if i is an integer and p is a pointer to an integer, then the statement p=&i initializes p by pointing it to i.

- The fourth way to initialize the pointer is to use the value zero. Zero is a special values used with pointers, as shown here: p = 0; or: p = NULL; What this does physically is to place a zero into p. The pointer p's address is zero. This is normally diagrammed as:

Any pointer can be set to point to zero. When p points to zero, however, it does not point to a block. The pointer simply contains the address zero, and this value is useful as a tag. You can use it in statements such as:

if (p == 0){ ...}

or:

while (p != 0){ ...}

The system also recognizes the zero value, and will generate error messages if you happen to dereference a zero pointer. For example, in the following code:

p = 0;*p = 5;

The program will normally crash. The pointer p does not point to a block, it points to zero, so a value cannot be assigned to *p. The zero pointer will be used as a flag when we get to linked lists.

The malloc command is used to allocate a block of memory. It is also possible to deallocate a block of memory when it is no longer needed. When a block is deallocated, it can be reused by a subsequent malloc command, which allows the system to recycle memory. The command used to deallocate memory is called free, and it accepts a pointer as its parameter. The free command does two things:

- The block of memory pointed to by the pointer is unreserved and given back to the free memory on the heap. It can then be reused by later new statements.

- The pointer is left in an uninitialized state, and must be reinitialized before it can be used again.

The free statement simply returns a pointer to its original uninitialized state and makes the block available again on the heap.

The following example shows how to use the heap. It allocates an integer block, fills it, writes it, and disposes of it:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

int *p;

p = (int *)malloc (sizeof(int));

*p=10;

printf("%d\n",*p);

free(p);

return 0;

}

This code is really useful only for demonstrating the process of allocating, deallocating, and using a block in C. The malloc line allocates a block of memory of the size specified -- in this case, sizeof(int) bytes (4 bytes). The sizeof command in C returns the size, in bytes, of any type. The code could just as easily have said malloc(4), since sizeof(int) equals 4 bytes on most machines. Using sizeof, however, makes the code much more portable and readable.

The malloc function returns a pointer to the allocated block. This pointer is generic. Using the pointer without typecasting generally produces a type warning from the compiler. The (int *) typecast converts the generic pointer returned by malloc into a "pointer to an integer," which is what p expects. The free statement in C returns a block to the heap for reuse.

The second example illustrates the same functions as the previous example, but it uses a structure instead of an integer. In C, the code looks like this:

#include <stdio.h>

struct rec

{

int i;

float f;

char c;

};

int main()

{

struct rec *p;

p=(struct rec *) malloc (sizeof(struct rec));

(*p).i=10;

(*p).f=3.14;

(*p).c='a';

printf("%d %f %c\n",(*p).i,(*p).f,(*p).c);

free(p);

return 0;

}

Note the following line:

(*p).i=10;

Many wonder why the following doesn't work:

*p.i=10;

The answer has to do with the precedence of operators in C. The result of the calculation 5+3*4 is 17, not 32, because the * operator has higher precedence than + in most computer languages. In C, the . operator has higher precedence than *, so parentheses force the proper precedence.

Most people tire of typing (*p).i all the time, so C provides a shorthand notation. The following two statements are exactly equivalent, but the second is easier to type:

(*p).i=10; p->i=10;

You will see the second more often than the first when reading other people's code.