The head of the British defense establishment and chairman of NATO's military committee, Air Marshall Sir Stuart Peach, recently warned that cutting the cables "would immediately — and catastrophically — fracture both international trade and the internet," according to the Guardian.

Peach's warning echoed the conclusions of a 2017 report written by U.K. Member of Parliament Rishi Sunak, which described the potential for disruption of internet traffic as an "existential threat." Sunak noted that the cables, which are largely owned and operated by private companies, transmit $10 trillion in financial transfers each day.

It's not the first time that an alarm has been sounded about the undersea cable networks. This 2010 report written for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, describes the effects of a 2008 incident in which three cables in the Mediterranean that connected Italy to Egypt were severed, apparently accidentally by commercial ships dragging their anchors. Eighty percent of the internet connectivity between Europe and the Middle East temporarily was lost. As a result, most of the U.S. Air Force's drone aircraft in Iraq were grounded, due to the lack of a reliable connection to technicians back in the U.S. "Cable breaks halfway across the world threaten U.S. vital national security interests," the report warned.

In 2015, The New York Times reported that a Russian spy ship, the Yantar, was kept under surveillance by U.S. planes, satellites and ships as it cruised slowly down the U.S. east coast, close to internet cables. The Russian ship reportedly was equipped with two miniature submarines capable of going into deep water to cut cables. Another Russian surveillance ship, the Viktor Leonov, was spotted off the coast of Delaware in February, according to the Christian Science Monitor.

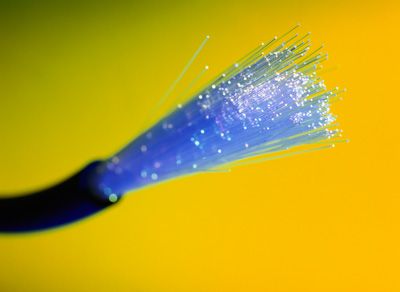

But before you get too caught up in a nightmare scenario of the internet suddenly going dark due to sabotage, experts say the system — despite its lack of defenses — is resilient and would be difficult for an enemy nation or terrorist group to disable. The fiber cables that transmit the world's data are surprisingly slim, measuring less than 0.7 inches (17 millimeters) in thickness, according to Keith Schofield, general manager of the International Cable Protection Committee, a British-based industry group. But the fiber is encased in a hermetically sealed tube, which is in turn surrounded by layers of high-tensile steel wires, copper and polyethylene. For sections in shallower water, where cables are more likely to encounter ship anchors and other manmade hazards, additional layers of armor are sometimes added, or else cables are buried under the seabed, Schofield says in an email.

As a result, cables are damaged worldwide only about 200 times a year — "a tiny failure rate across a network of well over a million kilometers (621,000 miles) of cable linking people between continents," Schofield says.

It would be difficult to cut cables in the deep ocean, though a robotic submersible equipped with the right tools could pull it off, says Jim Hayes, president of the Fiber Optic Association, a California-based professional society that certifies cable network builders and operators, in a telephone interview. The cable networks are more vulnerable closer to land, where their connections are in shallower water and easier to reach. It wouldn't take a lot of sophisticated weapons or know-how to inflict the desired damage.

"If you want to interrupt communications, you hire a crappy old fishing trawler, give them a big anchor and tell them to drag it here," Hayes explains.