For much of the music industry's lifetime, piracy wasn't a serious problem. From the onset of recorded sound through the 1960s, people bought vinyl records at record stores. They could listen to them at home and at gatherings and swap them with friends, but copying them would've been a difficult and expensive endeavor. Of course, a few people made bootleg records, but they were typically collections of outtakes or live performances the record companies had little interest in releasing -- some alternate recordings of Bob Dylan songs, for instance, or a cobbled-together version of the Beach Boys' album "SMiLE" that had yet to see the light of day.

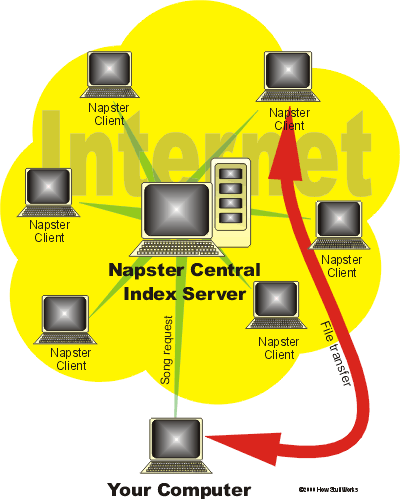

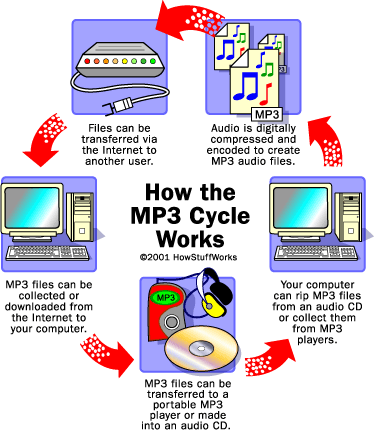

The advent of magnetic tape as a recording medium began to change things, primarily after blank microcassettes went on sale. Some recording industry executives took issue with people duplicating cassette tapes, but soon they had bigger problems to worry about -- especially when CDs arrived and sound became digital. CD burners allowed people to rip music off of CDs and onto personal computers. Add the Internet and peer-to-peer sites (P2P) to the equation, and record executives really started to worry. People were suddenly able to duplicate and share music with an almost unlimited number of users over the Internet, giving many the chance to download songs, albums, even entire discographies without paying a dime. With the value of music changing so rapidly, how would the music industry react?

Advertisement

Soon, record companies began selling "special" music CDs to consumers who thought they were getting ordinary compact discs. When people played these CDs on their computers, what happened in many cases was the equivalent of a spyware nightmare: Programs froze up, applications slowed and a series of hidden files that were the source of the problem proved to be nearly impossible to uninstall. Why would a company do this to its customers?

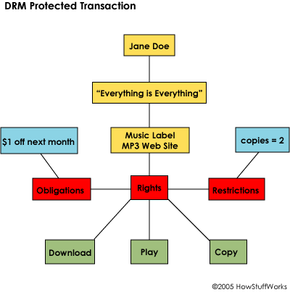

The answer comes down to copyright. The digital revolution that has empowered consumers to use digital content in new and innovative ways has also made it nearly impossible for copyright holders to control the distribution of their property. It's not just music, but film, video games and any other media that can be digitized and passed around. Digital rights management, or DRM, is a general term used to describe any type of technology that aims to stop, or at least ease, the practice of piracy. In this article, we'll find out what DRM is, how copyright holders are implementing the concept and what the future holds for digital content control.

Advertisement