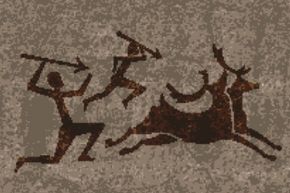

In incredible ways, the Internet has remade the way people communicate with one another. In centuries past, humans relied on word of mouth, handwritten letters, cave drawings, stone tablets and telegraph machines to convey messages and stories. Computers, satellites and cell phones have changed all of that. Text, pictures and videos all flow nearly instantaneously through the Web to just about anywhere on the planet.

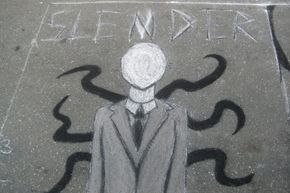

This fundamental shift in communication is altering our cultures and traditions in countless ways. It's also morphing our collective folklore. Folklore has a whole lot of definitions that change depending on whom you ask. But the New York Folklore Society has one of the most succinct. The society indicates that folklore is made up of "cultural ways in which a group maintains and passes on a shared way of life."

Advertisement

A group can be just two people. Or it can be millions. And they need to have only one common factor that links them, be it dance, song, food recipes, myths, exercise routines, pets, video games, chain letters, costumes or even graffiti. All group members typically have some idea of the core concepts of their subculture.

It's clear that the digital pathways of the Web are critical to modern-day folklore. How it's changed folklore is less certain. When the Web first gathered momentum in the early 1990s, a lot of folklorists (people who study folklore) bypassed this new technology as a source of material. Some of them felt the Web was too abstract – too coldly technological – to warrant deeper inquiry.

Nowadays, the 1990s are practically ancient history. The Web is deeply ingrained into all of our lives. It's an indisputable cultural force that's upended the way we communicate our most basic missives to family and friends. It's overturned the way we perceive the world all around us. And in many cases, although the Web allows for nearly unfettered and unthinkable levels of communication, it has also isolated us in ways that old means did not.

But we humans have an insatiable need to gather in groups and subdivisions of society, whether we do so in person or online. We tell stories that perpetuate our groups and lifestyles because we understand a particular way of life. The Internet is a valuable tool for helping all of us pass along not just technological tips and tricks, but traditions and legacies that last far longer than the latest memes or online fads.

Keep reading and you'll see how folklore is changing in the age of digital immediacy and shorter attention spans. You'll find out that our human need for lasting folklore is elastic and powerful even in the age of email and text messaging.

Advertisement