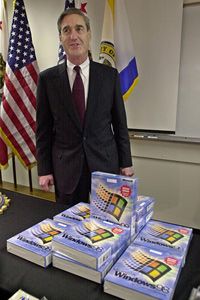

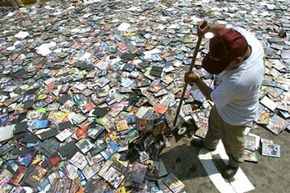

It's safe to assume that shortly after the first personal computers left store shelves, someone was plotting a way to get software for free. According to a report from Business Software Alliance (BSA), pirated software accounted for 41 percent of all software on PCs worldwide [source: BSA]. The BSA also reports that piracy costs software companies billions of dollars in revenue. Skeptics point out that software providers fund the BSA, making its findings suspect. Whether you believe BSA's statistic or not, it's true that piracy remains a big concern for software companies.

This concern has led companies to attempt to solve the problem through several different approaches with varying levels of success. Back in the early days of software -- piracy was around long before the Internet went public -- companies would include copy protection on their products. In some cases, this consisted of a few lines of code that made it difficult to copy the data from one medium onto another. But software protection took other forms as well: Many computer games would require the player to refer back to a game manual or other physical element that shipped along with the game.

Advertisement

Once the Internet and World Wide Web hit the scene, some companies began to experiment with various forms of digital rights management (DRM). Some DRM systems verify software by requiring a connection between the user and a remote server containing the DRM application. The big drawback to this method is that if the company goes out of business or decides to shut the server down, the software on your computer or mobile device suddenly becomes useless because there's no way to verify that you purchased it.

Not all DRM strategies are that extreme. But by its very nature, DRM places restrictions on the user. And because we've become accustomed to being able to manage our belongings any way we see fit, DRM isn't very popular with consumers. For example, in the United States, if you purchase a book, you have a right to sell your purchase. It's part of U.S. copyright law and is called the first-sale doctrine. But DRM restrictions often make it difficult, if not impossible, to sell a piece of software you've purchased and used. And it's much easier to create a copy of a program than it is a novel or magazine.

Could cheap software be the solution? If software didn't cost as much, would people be willing to buy more?

Advertisement